What I read this week

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor

A big existential question, especially for very commercially successful authors (luckily there aren’t that many, so we don’t have to worry about it too much) is what happens when one’s book is out in the world and open to interpretation by readers, especially if those readers are missing the entire point? This is what Nnedi Okorafor tackles in Death of the Author. It’s the story of Zelu, a disabled Nigerian American writer who writes a wildly successful sci-fi novel about the robots who inhabit Earth once the humans have died off.

I’m a sucker for a book within a book, but in this instance, it was Zelu’s own narrative that felt more propulsive than the segments of her book we get to read. But I think that’s the point. And if some of the little details feel off, like, for instance, the entirely magnanimous tech billionaire character who just wants to have adventures and not rob the Earth of all of its resources, well, that makes sense too if you read to the end.

The Secret History of the Rape Kit: A True Crime Story by Pagan Kennedy

It’s not entirely shocking to me that the inventor of the rape kit was a woman I’d never heard of and who never got credit for it. But Pagan Kennedy changes that in The Secret History of the Rape Kit, which is as much a love letter to a singular, complicated woman as it is to her invention. Marty Goddard had to play nice within the system while being unyieldingly persistent in order to make radical change. In the late 1970s and early 80s she had to talk to doctors and cops and lawyers and get them all to buy into the idea that rape is a crime just like murder and assault and robbery, and should be treated forensically as such. Marty played by the rules: she had the wardrobe of a respectable woman, no bra-burning for her. She couldn’t take credit for her idea to provide medical staff with tools to meticulously collect data from survivors in order to better find the culprits (not that she was after fame, but still). For many years the formal name of her invention was the Louis R. Vitullo kit, after the police sergeant Marty had approached with the idea.

It’s hard to believe that this mostly went down in the 1970s and 80s; before then, according to one nauseating passage, survivors of rape who sought help were made to hand all their clothing over to the police and in exchange they were given two hospital gowns and a pair of slippers to wear home (the police would drive them, at least). The reporting of rape has always been a humiliating, traumatizing process in itself, and Kennedy makes clear that despite Marty’s best efforts, we are still much farther from rectifying it decades later. I admire the open-endedness of Kennedy’s narrative; Marty’s work was just the start. We still have so much work to do.

There is no separating the art from the artist.

trigger warning: a bunch of sad, lurid details about sexual abuse of children below

I had been waiting a long time for Lila Shapiro’s sharp and painfully thorough reporting on Neil Gaiman to come out. I didn’t know the details, but I knew there was a lot of awful stuff coming. I know way too many details now. I am haunted by the details. They made me physically ill.

When the first accusations against Gaiman came out, I wrote about how posts on the Instagram account Xoxopublishinggg confirmed that younger people in publishing had already established a robust whisper network around Gaiman, even if it was the first time I learned it existed. So much of this story is about how a person can wear one face in front of you or his friends or his wider public, and a different one for others, often ones who are younger or more vulnerable or in sway of a rabid fandom. It’s a lesson we’ll have to keep learning again and again, I fear.

But the Gaiman story most reminded me of the excruciating, meticulously reported story that Rachel Aviv recently wrote in the wake of Alice Munro’s daughter’s Andrea accusing her mother of ignoring the fact that Munro’s partner had sexually abused Andrea as a child. That piece, too, made me feel ill, in large part because Aviv does such a thorough job of examining Munro’s work in light of her daughter’s accusations, including one story that was very explicitly billed as a story about “The Subject,” as she referred to it in a letter to her agent, Virginia Barber. So much of Andrea’s pain, we come to see, has been fodder for her mother’s creative endeavors. It’s too awful, and all of the wonderful stories of Alice Munro have become unreadable to me, a reader who had revered her.

I wasn’t a big Gaiman fan, just an admirer of his overall career and his recent work repping for the Writers Guild of America during their 2023 strike. I don’t know all of his stories, but I was struck by how Lila described them in her piece. So much of his work, it seems, contains details that are too painfully recognizable from his own life — most glaringly, the 7 year-old charge in The Ocean at the End of the Lane who witnesses his monstrous nanny having sex with his father. The 7 year-old boy was meant to be a stand-in for Gaiman as a child, but, as we learn in Lila’s piece, it’s the father of the boy who is uncomfortably like Gaiman now. We learn of a few instances in which Gaiman raped women in the presence of his child. It’s too much.

In Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, the great Clare Dederer argues that what we know of an artist’s misdeeds stains his work. We can still love a Roman Polanski film or a Miles Davis album because they are works of genius, but what we know about their creator’s sticks with us just the same. Their art is tinged by association with their personal histories.

But I think the cases of Munro and Gaiman open up a new question: what do we do with art once we learn that it depicts situations that are explicitly similar to the transgressions of the author? I haven’t donated or thrown away my Alice Munro books, yet. But I know I don’t want to pick them up again.

And as for Gaiman, the self-proclaimed feminist accused of rape whose main character in the comic book series The Sandman is a rapist? Vulture has started keeping track of all of Gaiman’s halted and canceled projects, all of which are TV projects, for now. Will any of his book publishers speak out or cancel projects (and will Skyhorse then pick him up a la Blake Bailey)? It remains to be seen.

I’m gonna include a link to RAINN here. Be good to yourself.

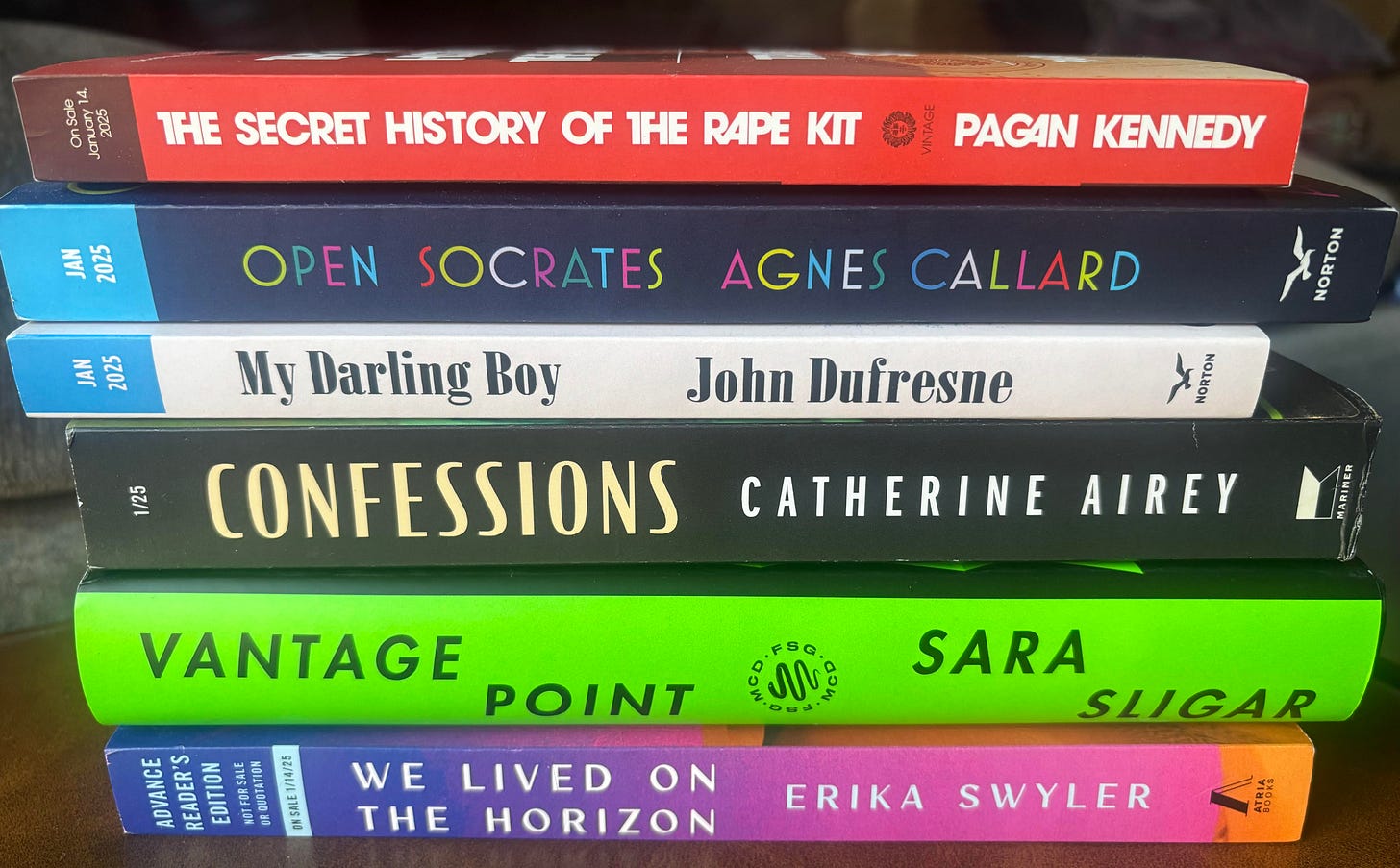

New releases, 1/14/25

Death of the Author by Nnedi Okorafor (see above)

The Secret History of the Rape Kit: A True Crime Story by Pagan Kennedy (see above)

Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life by Agnes Callard

My Darling Boy by John Dufresne

Confessions by Catherine Airey

Vantage Point by Sara Sligar

We Lived on the Horizon by Erika Swyler

Dirtbag Queen by Andy Corren

Karma Doll by Jonathan Ames

Good Girl by Aria Aber

Good Girl is a beautifully written work of literary fiction about art and identity and belonging, but it’s also very much a horror novel: there were so many times when the heroine would make a choice that would make me scream, “NO! Don’t go in there! RUN!” It doesn’t help that Good Girl’s almost 19 year-old heroine, Nila, becomes preoccupied with an American writer she meets at a club and who sucks in so many obvious ways. He’s a has-been, a man-child, a prick, a narcissist, and Nila can’t resist. It reminded me of one of those all-consuming, dramatic, unhealthy relationships that you look back on and think, “Damn, what a loser” and you’re referring both to the other person and to yourself.

An aspiring photographer, Nila spends more time navigating a decadent late night/early morning techno scene. In the current moment she’s living back at home with her father and taking courses at a local university after graduating from a boarding school where she was a scholarship student. The daughter of Afghani refugees, Nila lives in German public housing in a community of fellow exiles, and she bristles at the way its inhabitants judge and police the choices of women. What better way to rebel against a culture that values “good girl”s than by sleeping with older (loser) men, by doing drugs, by being really into techno and the culture that surrounds it? (We know she turns out okay because she’s narrating from a later time.)

With its depictions of the decadence of late nights (or early mornings) in Berlin’s techno scene, Good Girl is a bildungsroman by way of Berghain, with our hero’s great transformation sped up to take place over the course of one tumultuous year.

I'm excited to read Ms. Okorafor's new novel. She never disappoints and sees the world with such clear vision.

Thank you for continuing to write about Gaiman. It's such a difficult story.